HALIBUT RESEARCH: Part I

The first part of this research focuses on interactions that commercial fishermen have with bycatch species while targeting halibut. The following is a presentation that was given at the Alaska Marine Science Symposium in Anchorage, Alaska, during January 2017. Please contact ecfigus@alaska.edu for reference and citation information.

Read the page for slide descriptions. Click on the photos for an enlarged slideshow version.

How we collect information about marine species is a crucial part of managing our marine environment to ensure a sustainable future for fish and for humans. In commercial fisheries management, fisheries scientists have spent many decades focusing data collection and analysis efforts on commercially important target species without always addressing the fuller picture of the marine ecosystem. Today we understand the importance of multi-species perspectives and ecosystem dynamics, yet we remain constrained in our abilities to gather information. This research is about data collection in the commercial halibut fishery, and what the observations of fishermen can tell us.

Pacific halibut is a demersal, right-eyed flounder species, with a wide range (roughly from California to Japan). As you can see from the map below, halibut’s range covers all of the AK coastline south of the Bering Strait. Halibut are apex predators that are relatively slow-growing (reaching maturity between 8 and 12 years of age) and are relatively long-lived (with some indviduals living into their 50s). Halibut are one of the largest teleost fishes in the world. They are able to grow to over 400 pounds and 8 feet length, and today, there are important subsistence, sport, and commercial fisheries for halibut in Alaska.

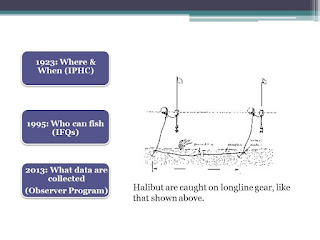

The history of commercial halibut fishing in Alaska goes back to the 1890s, and includes a multitude of fisheries management decisions. For the purposes of our research, three key management measures must be understood...The first management measure took place in 1923, when Pacific halibut stocks first became jointly researched and managed through an international agreement between the US and Canada. This joint body is called the International Pacific Halibut Commission, or the IPHC. At that time, back in 1923, the halibut fishery first became limited in terms of where and when fishermen were allowed to go fishing. The second key management measure occurred in 1995, with the introduction of individual fishing quotas, or IFQs. IFQs essentially privatize the right to fish, which controls who can fish. The third and most recent change I would like to highlight, took place in 2013, when the halibut fishery became incorporated into the federal observer program. This altered how fishermen are monitored out on the fishing grounds. Our research addresses this third key regulatory shift.

The Observer Program offers the opportunity to systematically collect data about species encountered at sea by halibut fishermen, but not landed. These are called discards. The IPHC has been gathering bycatch data in their own independent setline survey for decades, but it is uncertain to what extent this reflects patterns in the directed fishery.

All halibut vessels are classified within the partial coverage category. This means that IFQ-holders, the fishermen, must register to be randomly selected for hosting an observer on a trip basis, with vessels under 40 feet in length overall currently exempted from selection. The observer program is extensive, and far-reaching, and it functions a bit differently for each fishing fleet. However, in the halibut fleet the program offers a way to fill an existing data gap. Through the IPHC and regulations related to IFQs, managers currently have access to detailed landings and stock assessment data. What they have been missing is a detailed understanding of commercial discards at-sea.

Observers are one way to gather more comprehensive data from the directed fishery, with the potential to provide a representative snapshot of interactions that fishermen have with all species in the ocean while targeting halibut. However, the new observer program is costly and has been met with some dissatisfaction, as well as a series of logistical challenges of deploying human observers on small vessels. The Program is currently limited to working on vessels over 40 feet in length, and achieving statistically representative deployment has proved difficult. In response to these challenges, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council has made steps to implement an electronic monitoring option in the halibut fleet. Results from a hybrid data gathering program likely remain many years out from becoming a reality.

In light of the challenges faced during implementation of the restructured Observer Program, our research uses the observations and knowledge of fishermen to fill in some important data gaps (read slide). This research takes a deeper look at a subset of halibut fishermen, to document their experiences with bycatch and compare those experiences with IPHC data, across characteristics such as vessel length, gear type, and season of the year fished. We took an in-depth look at fishermen in southeast Alaska as a group, and compared their fishing observations with the IPHC.

Do fishermen and the IPHC experience similar trends in bycatch over space and time?

Is the observer program likely to document differences in bycatch not previously recorded?

How do different fishing practices affect bycatch composition?

To achieve our objectives, we conducted interviews with halibut fishermen residing in four communities in Southeast Alaska: Hoonah, Juneau, Petersburg and Sitka. Interviewees composed an average of 20% of total IFQ shares in their corresponding communities of residence. Additionally, interviewees were almost exactly reflective of quota classes, or types of quota, in their communities.

Fishermen were asked to reflect on the mix and prevalence of species observed on their halibut skates. During interviews, we asked them to sort cards representing 51 bycatch species into bins to reflect how often they encountered each one. Species were determined during test interviews with 9 fishermen in Haines, AK, as well as including those known from IPHC surveys. Additional questions explored fishermen’s experiences with how bycatch varies over season, years of experience, vessel length, whether or not they combo fish for black cod and halibut at the same time, etc.

Interview data were combined with data from annual IPHC setline surveys to compare observations of fishermen with scientific findings. 92 stations from the setline survey in management area 2C in southeast Alaska were analyzed for the years 1998-2015. IPHC observations were analyzed against both the full group of interviewees as well as across the four communities. The map on the left shows an example of IPHC survey stations in the Baranof Island area of Southeast Alaska. The map on the right shows an example of areas fished by interviewees.

We explored ways to combine information from fishermen with observations from scientists. The data are a mix of qualitative and quantitative observations, and they tend to violate assumptions of normal distribution. What Dr. Criddle and I have been able to do so far is to combine multiple methods for analysis, with each method describing part of a larger picture. We used the four methods on the left to look at a comparison of fishermen and IPHC observations, based on 7 fishing characteristics shown on the right.

Chi-square tests of independence and analysis of variance allowed us to determine (read slide). The chi-square test is a simple test of independence, and cannot explain causality, however, it begins to fill in some of the information about shifts in bycatch across space and time. These could only be run on the interview data, since qualitative and quantitative observations cannot be mixed.

Chi-square tests indicated that combo fishermen in the group were more likely to have fished in spring than other fishermen or the IPHC; this suggests that to understand differences in bycatch patterns seasonally, we need to ensure that differences are not artifacts of combo or non-combo fishing; the same appears to be possible for gear types and vessel length.

An analysis of variance indicated that community of residence was significantly related to IPHC stations fished across the four study communities. This suggests that residents in Hoonah and Juneau exhibit a statistically significant tendency to fish around more northern IPHC stations (closer to their corresponding communities), while residents of Sitka and Petersburg tend to fish around more southern IPHC stations. Additionally, visual review of stations fished by more than one respondent from each community overlayed on a map of Southeast Alaska shows that fishermen from Hoonah and Juneau have a smaller spatial fishing range than residents of Sitka and Petersburg, with Petersburg residents exhibiting the broadest halibut fishing range. These findings hint that multivariate analyses may help tease out relationships among encounters with bycatch species and fishing characteristics.

Multiple Factor Analysis was used to explore how fishing characteristics impact bycatch prevalence. MFA can tell us which things seem to be related to one another, by indicating how bycatch species and fishing characteristics group across dimensions of the data.

By normalizing the values for IPHC and from interviews, it was possible to compare them in the FactoMineR program in R software. For this exercise, we wanted to be able to compare across fishing characteristics, so we grouped IPHC observations by stations corresponding to the stations used by residents of each community.

Reducing our set of bycatch species to 22 of management interest and high encounter rate allowed us to look at how fishing characteristics relate to encounters with bycatch, without failing the Keyser-Meyer-Olkin Test for sampling adequacy. Results from a parallel analysis further indicated 8 dimensions for retention to explain variance in the dataset.

A few examples of the relationships that can be explored using this technique are shown below.

MFA output can graphically map observations into latent orthogonal factors that represent commonalities among variables and across observations. For this MFA, if we look at comparisons among the first and second dimensions of fishing characteristics, we can see that vessel length on the bottom right is strongly associated with the first dimension, community of residence and the species encountered on the top left are associated with the second dimension, and whether a fisherman uses conventional or snap-on gear in the middle is associated with both the first and second dimensions. Years of fishing experience, on the other hand, has no influence on either dimension.

When we look at the bycatch species, MFA output suggests that species group across the first two dimensions, with vessel length playing a strong role, but fishing experience having no influence.

Read the page for slide descriptions. Click on the photos for an enlarged slideshow version.

How we collect information about marine species is a crucial part of managing our marine environment to ensure a sustainable future for fish and for humans. In commercial fisheries management, fisheries scientists have spent many decades focusing data collection and analysis efforts on commercially important target species without always addressing the fuller picture of the marine ecosystem. Today we understand the importance of multi-species perspectives and ecosystem dynamics, yet we remain constrained in our abilities to gather information. This research is about data collection in the commercial halibut fishery, and what the observations of fishermen can tell us.

Pacific halibut is a demersal, right-eyed flounder species, with a wide range (roughly from California to Japan). As you can see from the map below, halibut’s range covers all of the AK coastline south of the Bering Strait. Halibut are apex predators that are relatively slow-growing (reaching maturity between 8 and 12 years of age) and are relatively long-lived (with some indviduals living into their 50s). Halibut are one of the largest teleost fishes in the world. They are able to grow to over 400 pounds and 8 feet length, and today, there are important subsistence, sport, and commercial fisheries for halibut in Alaska.

The history of commercial halibut fishing in Alaska goes back to the 1890s, and includes a multitude of fisheries management decisions. For the purposes of our research, three key management measures must be understood...The first management measure took place in 1923, when Pacific halibut stocks first became jointly researched and managed through an international agreement between the US and Canada. This joint body is called the International Pacific Halibut Commission, or the IPHC. At that time, back in 1923, the halibut fishery first became limited in terms of where and when fishermen were allowed to go fishing. The second key management measure occurred in 1995, with the introduction of individual fishing quotas, or IFQs. IFQs essentially privatize the right to fish, which controls who can fish. The third and most recent change I would like to highlight, took place in 2013, when the halibut fishery became incorporated into the federal observer program. This altered how fishermen are monitored out on the fishing grounds. Our research addresses this third key regulatory shift.

The Observer Program offers the opportunity to systematically collect data about species encountered at sea by halibut fishermen, but not landed. These are called discards. The IPHC has been gathering bycatch data in their own independent setline survey for decades, but it is uncertain to what extent this reflects patterns in the directed fishery.

All halibut vessels are classified within the partial coverage category. This means that IFQ-holders, the fishermen, must register to be randomly selected for hosting an observer on a trip basis, with vessels under 40 feet in length overall currently exempted from selection. The observer program is extensive, and far-reaching, and it functions a bit differently for each fishing fleet. However, in the halibut fleet the program offers a way to fill an existing data gap. Through the IPHC and regulations related to IFQs, managers currently have access to detailed landings and stock assessment data. What they have been missing is a detailed understanding of commercial discards at-sea.

Observers are one way to gather more comprehensive data from the directed fishery, with the potential to provide a representative snapshot of interactions that fishermen have with all species in the ocean while targeting halibut. However, the new observer program is costly and has been met with some dissatisfaction, as well as a series of logistical challenges of deploying human observers on small vessels. The Program is currently limited to working on vessels over 40 feet in length, and achieving statistically representative deployment has proved difficult. In response to these challenges, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council has made steps to implement an electronic monitoring option in the halibut fleet. Results from a hybrid data gathering program likely remain many years out from becoming a reality.

In light of the challenges faced during implementation of the restructured Observer Program, our research uses the observations and knowledge of fishermen to fill in some important data gaps (read slide). This research takes a deeper look at a subset of halibut fishermen, to document their experiences with bycatch and compare those experiences with IPHC data, across characteristics such as vessel length, gear type, and season of the year fished. We took an in-depth look at fishermen in southeast Alaska as a group, and compared their fishing observations with the IPHC.

Do fishermen and the IPHC experience similar trends in bycatch over space and time?

Is the observer program likely to document differences in bycatch not previously recorded?

How do different fishing practices affect bycatch composition?

To achieve our objectives, we conducted interviews with halibut fishermen residing in four communities in Southeast Alaska: Hoonah, Juneau, Petersburg and Sitka. Interviewees composed an average of 20% of total IFQ shares in their corresponding communities of residence. Additionally, interviewees were almost exactly reflective of quota classes, or types of quota, in their communities.

Fishermen were asked to reflect on the mix and prevalence of species observed on their halibut skates. During interviews, we asked them to sort cards representing 51 bycatch species into bins to reflect how often they encountered each one. Species were determined during test interviews with 9 fishermen in Haines, AK, as well as including those known from IPHC surveys. Additional questions explored fishermen’s experiences with how bycatch varies over season, years of experience, vessel length, whether or not they combo fish for black cod and halibut at the same time, etc.

Interview data were combined with data from annual IPHC setline surveys to compare observations of fishermen with scientific findings. 92 stations from the setline survey in management area 2C in southeast Alaska were analyzed for the years 1998-2015. IPHC observations were analyzed against both the full group of interviewees as well as across the four communities. The map on the left shows an example of IPHC survey stations in the Baranof Island area of Southeast Alaska. The map on the right shows an example of areas fished by interviewees.

We explored ways to combine information from fishermen with observations from scientists. The data are a mix of qualitative and quantitative observations, and they tend to violate assumptions of normal distribution. What Dr. Criddle and I have been able to do so far is to combine multiple methods for analysis, with each method describing part of a larger picture. We used the four methods on the left to look at a comparison of fishermen and IPHC observations, based on 7 fishing characteristics shown on the right.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to explore the strength of correspondence among interviewee responses.

Preliminary findings indicate that what fishermen expect to see and what the IPHC counts on their setline survey are positively correlated. There are no significant negative correlations among interviewees in the group. The same trend holds true across seasons. This suggests that the fishermen interviewed had similar experiences with bycatch species to another. What one fisherman sees tends to be a pretty good representation of the species everyone else sees. This also suggests that the fishermen interviewed and the IPHC have had similar experiences with bycatch. Furthermore, although the IPHC conducts their survey during the summer, there was no indication that bycatch varies at the species level by season. There was no indication that the IPHC was missing general, major trends in bycatch prevalence across all 51 species before the Observer Program began collecting bycatch data in the halibut fleet in 2013. However, the gray areas on these correlograms indicate the potential for varied experiences with some bycatch species across fishermen. Chi-square tests of independence and analysis of variance allowed us to determine (read slide). The chi-square test is a simple test of independence, and cannot explain causality, however, it begins to fill in some of the information about shifts in bycatch across space and time. These could only be run on the interview data, since qualitative and quantitative observations cannot be mixed.

Chi-square tests indicated that combo fishermen in the group were more likely to have fished in spring than other fishermen or the IPHC; this suggests that to understand differences in bycatch patterns seasonally, we need to ensure that differences are not artifacts of combo or non-combo fishing; the same appears to be possible for gear types and vessel length.

An analysis of variance indicated that community of residence was significantly related to IPHC stations fished across the four study communities. This suggests that residents in Hoonah and Juneau exhibit a statistically significant tendency to fish around more northern IPHC stations (closer to their corresponding communities), while residents of Sitka and Petersburg tend to fish around more southern IPHC stations. Additionally, visual review of stations fished by more than one respondent from each community overlayed on a map of Southeast Alaska shows that fishermen from Hoonah and Juneau have a smaller spatial fishing range than residents of Sitka and Petersburg, with Petersburg residents exhibiting the broadest halibut fishing range. These findings hint that multivariate analyses may help tease out relationships among encounters with bycatch species and fishing characteristics.

Multiple Factor Analysis was used to explore how fishing characteristics impact bycatch prevalence. MFA can tell us which things seem to be related to one another, by indicating how bycatch species and fishing characteristics group across dimensions of the data.

By normalizing the values for IPHC and from interviews, it was possible to compare them in the FactoMineR program in R software. For this exercise, we wanted to be able to compare across fishing characteristics, so we grouped IPHC observations by stations corresponding to the stations used by residents of each community.

Reducing our set of bycatch species to 22 of management interest and high encounter rate allowed us to look at how fishing characteristics relate to encounters with bycatch, without failing the Keyser-Meyer-Olkin Test for sampling adequacy. Results from a parallel analysis further indicated 8 dimensions for retention to explain variance in the dataset.

A few examples of the relationships that can be explored using this technique are shown below.

MFA output can graphically map observations into latent orthogonal factors that represent commonalities among variables and across observations. For this MFA, if we look at comparisons among the first and second dimensions of fishing characteristics, we can see that vessel length on the bottom right is strongly associated with the first dimension, community of residence and the species encountered on the top left are associated with the second dimension, and whether a fisherman uses conventional or snap-on gear in the middle is associated with both the first and second dimensions. Years of fishing experience, on the other hand, has no influence on either dimension.

When we look at the bycatch species, MFA output suggests that species group across the first two dimensions, with vessel length playing a strong role, but fishing experience having no influence.

In this project, we have looked at how to combine qualitative

information from fishermen with quantitative data from the IPHC; we

conclude that (read slide).

In the example of Southeast Alaska, there appear to be commonalities

in the experiences of fishermen and the IPHC, and even relatively small

samples can be characteristic of experiences that fishermen have with

bycatch. Increased

data collection may not identify

previously unknown trends

in

overall bycatch prevalence, but may identify previously

undocumented finer-scale trends. Accounting for fishing characteristics may increase the accuracy of fine-scale data collection throughout the fleet.

Comments

Post a Comment